There’s a certain trick to looking at an Oliviero Toscani photograph, and the trick is that you can’t just look. You have to react. Your stomach tightens, your pupils constrict, your hands involuntarily curl into little fists of unease or intrigue or outright discomfort. Toscani’s work—if we are willing to call it just that, as opposed to some more metabolically unstable amalgam of commercialism and art and provocation and dare-you-to-look-away confrontation—is less about what’s on the glossy surface of the image than about what detonates in the viewer’s brain upon exposure.

To say that Toscani has disrupted the status quo of advertising is like saying the Trojan horse ‘complicated’ the security policy of ancient Troy. His work, particularly for Benetton in the 1980s and 90s, didn’t just nudge the industry toward a reconsideration of ethics in branding—it torched the whole orchard, salted the earth, and dared the world to find another way to sell sweaters without pretending everything was fine. Because, and this is one of the core tenets of Toscani’s brand of visual terrorism, everything is not fine.

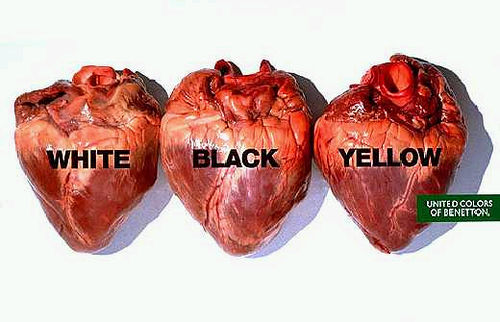

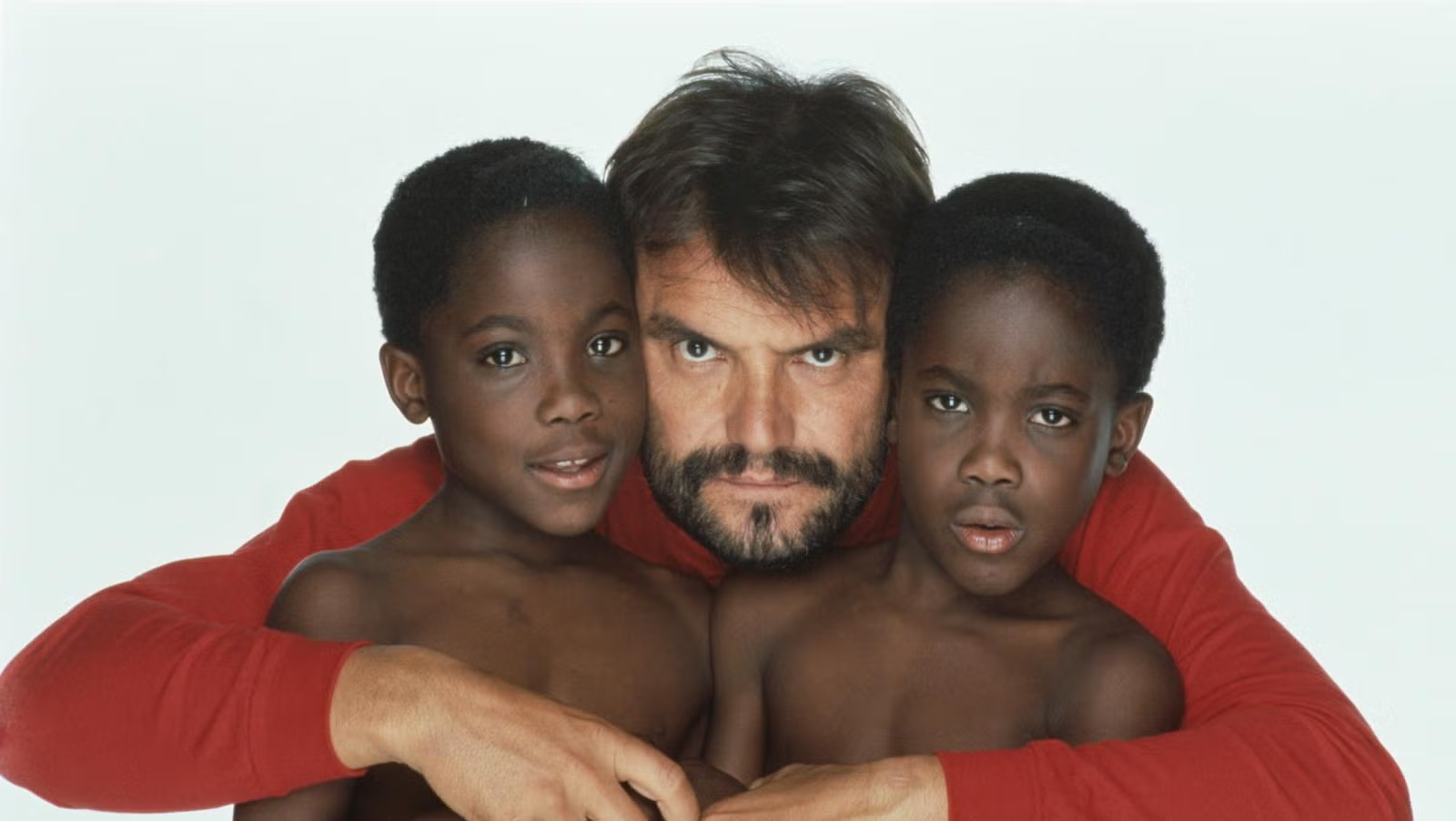

A quick refresher: Toscani’s campaigns for Benetton featured dying AIDS patients, blood-stained uniforms of fallen soldiers, a priest kissing a nun, inmates on death row—images that, unlike the anodyne utopia of most advertising, refused to let the consumer remain a consumer alone. The photographs weaponized the glossy sheen of commercial photography, trapping the viewer in a moral interrogation chamber. Were you looking at an ad? A protest? A cynical appropriation of pain for profit? All three?

And this, right here, is where Toscani’s work exceeds the limits of mere controversy and enters the domain of the truly disruptive: he refuses, utterly and without compromise, to allow an easy distinction between the aesthetic and the ethical. The viewer, instead of luxuriating in aspirational fantasy, must reckon with a kind of violently democratized gaze—an image that doesn’t just offer itself up as desirable, but as unignorable. Toscani’s work forces its own presence into your neural pathways, into the anxious thrum of your cultural awareness, refusing the traditional contract of advertising where one desires and the other provides the illusion of fulfillment. His photographs don’t seduce; they demand.

Which, not incidentally, is why his images remain lodged in the collective unconscious long after their initial run in glossy magazines or billboards. Toscani doesn’t merely comment on the intersection of politics and commerce—he makes that intersection unavoidable. He drags real-world violence, real-world suffering, and real-world ethical crises into the antiseptic realm of high fashion and consumer goods, as if to say: Here. You can’t pretend you didn’t see this. You can’t unknow it. Now, what will you do?

The deeper, almost vertiginous brilliance of Toscani’s method is that, while his critics accuse him of exploitation, he forces that same question back onto the entire machinery of capitalism itself. If Toscani exploits suffering to sell sweaters, then what, exactly, does conventional advertising do when it exploits desire, loneliness, insecurity, and self-image? Is the commodification of human pain any worse than the commodification of human aspiration? Or are they, perhaps, part of the same system, just wearing different masks? Toscani, in his relentlessly uncompromising way, compels us to admit that this is not a pleasant question to ask, nor an easy one to answer.

And so, the Toscani paradox: an artist who manipulates the tools of commercial seduction to obliterate commercial complacency. A photographer who turns the traditionally passive act of looking into an act of reckoning. A provocateur whose best work functions not as an image, but as an accusation. It is, frankly, a lot to take in.

Which is precisely the point.