“Embroidery was the love of writing your dreams with a needle, with a pearl, with anything that could enchant and bring tenderly to life a décor, an ambiance, a souvenir.” François Lesage

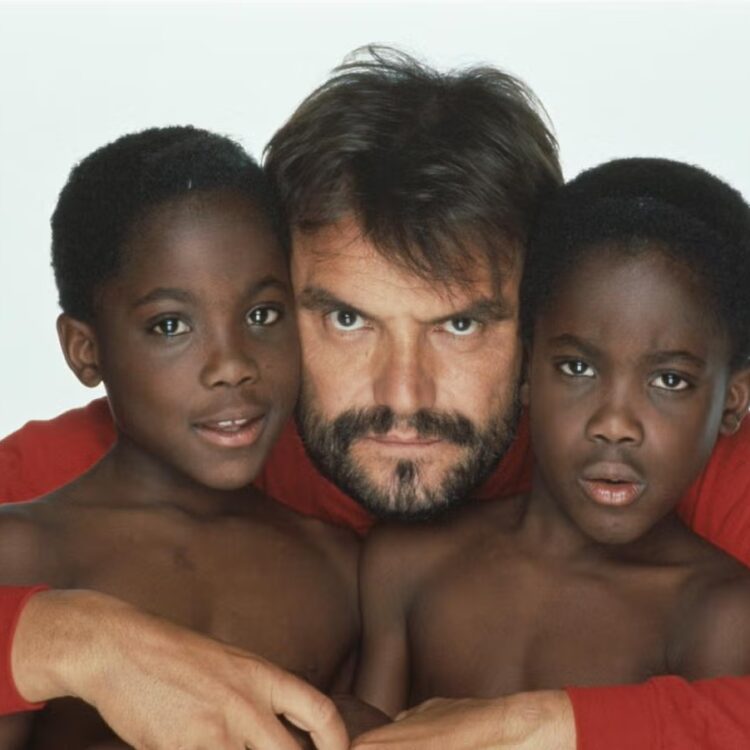

His father, Albert, founded the family firm in 1924 when he bought the atelier of Napoleon III’s embroiderer, Michonet, who had also worked for Charles Frederick Worth. Subsequently Albert married Marie-Louise Favot, an embroidery worker at Vionnet.

The business came with a glittering mountain of beads, and the couple’s son, François, was born on March 31 1929, “on a heap of pearls”, as he put it.

As a baby he was bounced on Madeleine Vionnet’s knee and he could remember, as a child, queuing up with his father like a tradesman at the back doors of Balenciaga and Schiaparelli. But life, especially during the war years, was not easy: “When I was 15 it was my responsibility to go around to all the fashion houses and ring the bell to ask for payment,” he recalled. “Sometimes they were obliged to sell their paper patterns to pay the accounts.”

François created his first embroidery in 1946 while his parents were away on holiday. At that point an important Italian client turned up demanding a dress inspired by Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. François was studying Philosophy at the Collège Saint-Jean de Béthune at the time, but whipped up a flower design based on the painting.

The following year he was sent off to Los Angeles to learn English. There he met Lauren Bacall, Claudette Colbert and Lana Turner (with whom he claimed to have had an affair). In 1948, using his father’s samples, he set up his own embroidery business on Sunset Boulevard, where he produced dresses for Ava Gardner and Marlene Dietrich and worked with Edith Head and other film designers.

In 1949 his father died, and François returned to Paris to take over the family business. As post-war austerity turned into post-war boom Maison Lesage, a rabbit warren of rooms at 13 rue de la Grange Batelière, began to hum with industry. But he found that, whereas in America all he had had to do was adapt his father’s designs, in France things were different: “I had to learn that in business we don’t impose anything on the designers. They want to be the origin of everything.”

Over the next 60 years Lesage worked with such designers as Pierre Balmain, Hubert de Givenchy, Christian Dior, Cristobal Balenciaga and Karl Lagerfeld, as well as with the Americans Calvin Klein, Bill Blass, Geoffrey Beene and Oscar de la Renta. He created well over 65,000 designs to be worked into glittering perfection by his staff of highly skilled “petites mains” — the women artisans who transform a design into a sumptuous showpiece of luxury, hand-stitching sequins, tiny beads, rhinestones, shells, ribbons and feathers to pieces of exquisite fabric.

It was Lesage who produced the sparkly grape bunches on satin jackets that won Yves Saint Laurent a standing ovation at his 1988 winter couture collection. “Fabulous, like wind through the vines,” Saint Laurent told him when he saw the design. Other famous Lesage designs included “chess game” jackets for Chanel.

He became adept at interpreting the often vague, sometimes outlandish, instructions of couturiers, refusing commissions unless he could meet them face to face: “I have to see the designer, the sparkle in the eyes. I have to undress the mind,” he once explained.

When Saint Laurent asked for “something that is like a chandelier reflecting off the mirror with the sky of Paris in the background”, Lesage knew exactly what he meant. When Schiaparelli asked for shells, the entire atelier ate mussels all winter. Other extraordinary designs included rhinestone-studded nets trapping fresh asparagus for Jacques Fath, and a Saint Laurent dress embroidered with overlapping “fish scales” of paillettes for Soraya Khashoggi.

Lesage always did his best to go along with his clients’ whims. When Thierry Mugler asked for a “trashy beach”, the Lesage embroiderers went to work stitching pull tabs and bottles out of sequins and beads on an evening gown. But there were limits. When Mugler asked him to add in some condoms, Lesage decided that enough was enough — “but we did make two of those dresses: one for the runway and one for Tina Turner”.

Lesage always did his best to go along with his clients’ whims. When Thierry Mugler asked for a “trashy beach”, the Lesage embroiderers went to work stitching pull tabs and bottles out of sequins and beads on an evening gown. But there were limits. When Mugler asked him to add in some condoms, Lesage decided that enough was enough — “but we did make two of those dresses: one for the runway and one for Tina Turner”.

Lesage’s work did not come cheap: his embroideries typically translated into $100,000-$150,000 for a gown or $60,000 for a jacket. Exceptional pieces included a gown with a 20-metre train, for which the embroidery alone cost $1.6 million, and a coronation dress for an African empress, which took 11,000 hours of work. “Some things you can’t quibble over,” Lesage observed. “It’s like asking the price of a custom-made car.”

In a recent interview, Lesage observed that after 60 years of dealing with fashion egos, he could be an ambassador at the United Nations. About the only couturier he did not work for was Alexander McQueen. “We had a misunderstanding about one dress,” Lesage explained. “So now, I’m punished!”

During the high-rolling 1980s, Maison Lesage employed more than 100 embroiderers, but in the early 1990s it came close to closure when the 1991 Gulf War diminished its core customer base of Middle Eastern royalty.

The business ate up 40 years of savings in just a few years as demand dropped off; Lesage was forced to cut the workforce by around half and, in an attempt to ensure the future of the company, opened his own embroidery school.

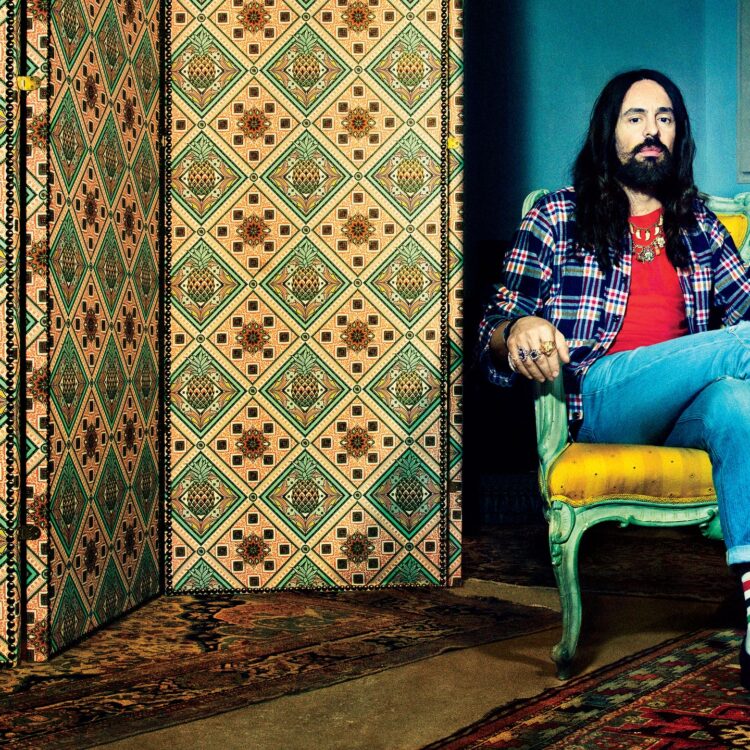

Though demand picked up later with the development of the market for luxury products in countries such as India, China, Russia and Brazil, Lesage began to feel the heat from cheaper embroidery producers in the developing world. In 2002 Chanel bought up five of the industry’s key suppliers, including Lesage.

A bon vivant who smoked French cigarettes and boasted that he did not know how to sew on a button, Lesage continued to work into his 80s. In 2007 he was made an officer of the Légion d’honneur, and a week before his death was awarded the honorary title of Maître d’art by the French minister of culture Frédéric Mitterrand.

François Lesage was married and had four children, but, as he once explained: “I’m married, but I have girlfriends. I’m French; it’s in my blood.” He could write a book about his life, he said — “but it would be X-rated!”

Article: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/8932330/Francois-Lesage.html